By David Abel | Globe Staff | 9/16/2002

The rows of vinyl seats where she used to sleep are all gone. New checkpoints have blocked off a few preferred nooks and the mood has changed, with stocky officers in black fatigues and combat boots holding large, menacing rifles.

There's something else different about Logan Airport - a lingering eeriness, a missing excitement, and most egregious of all for her, a disappeared community.

Before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Judie Jones and at least a half-dozen elderly women spent nearly every night blending in with travelers and sleeping in secret spots throughout the terminals. A year later, with the size of the security staff doubled and the airport enforcing an old rule barring the homeless, few if any of the women have returned.

The changes have upset Jones, a short, Shakespeare-quoting 67-year-old who calls Logan her home. But the chain-smoking native of Australia doesn't blame airport officials or the once-dreaded troopers, who she now says are "beautiful to watch." The blame, she says, squarely lies with "that swine, bin Laden," whom she calls a "hurricane of hysteria" and a "pusillanimous excrescence."

"On Sept. 11 last year, you broke my heart and the heart of every decent, law-abiding American," she wrote to him in an "open letter" from "the lady who loves Logan."

In another missive to the wanted Al Qaeda leader, she added, "It's not so much what you've done to a group of homeless people. We'll survive. But how dare you change the fun, the bustle, and the excitement that was Logan!"

For years, especially during the winter, the state troopers at Logan often looked the other way when running into Jones and the other women they had come to know. Others, who presented problems, were often put in cabs and sent to shelters, as the airport's policy instructed. But since the attacks, the airport has maintained something close to a zero-tolerance policy.

"It's a whole new ballgame here," said Phil Orlandella, a Logan spokesman. "I don't think anyone looks the other way anymore. We get calls now for anyone who looks or acts suspiciously - and sometimes those people are homeless. We have to be careful."

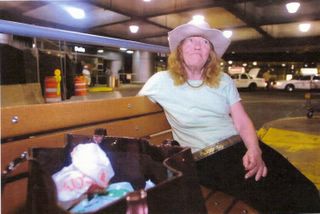

On a recent night at Logan, Jones, wearing a large felt Stetson,

a pair of well-worn flip-flops, and a gold necklace over a lime blouse, lugged two handbags, searched ashtrays for cigarette butts, and, as has long been her custom, hunted for abandoned Smarte Cartes, returning each for a quarter. "It's good fun, like the poker machines in Vegas," she said.

a pair of well-worn flip-flops, and a gold necklace over a lime blouse, lugged two handbags, searched ashtrays for cigarette butts, and, as has long been her custom, hunted for abandoned Smarte Cartes, returning each for a quarter. "It's good fun, like the poker machines in Vegas," she said.Picking up a half-filled cup of ice coffee someone left for trash, and between puffs of a whole cigarette from a friend, she winked and said, "I can see why I might be vaguely suspicious."

The outspoken woman with bright blue eyes, auburn hair, and creased cheeks that frame a nearly toothless smile says she has returned to the airport because people there treat her like "an international traveler, a human being who they call ma'am.' " It's also a way of earning as much as $15 a day returning carts.

"If I had my choice, I would live here again," she said.

To visit for the day is one thing. To return to sleep, though, is too risky - she's afraid she might get arrested.

On Sept. 11, 2001, when she learned about the hijackings while at a job conference, it began to dawn on her that she too would be directly affected. Her home would be locked down with security forces, she worried, ready to shoot at anyone who didn't seem to belong.

"Under no circumstances would I go to the airport - it was too scary," she said. "Who knows what would have happened?"

That night, and through the spring, Jones, who speaks French and German and once studied Latin, stayed at the city's homeless shelter on Long Island. After feeling confined, complaining about her living conditions, and running into problems with the shelter's staff, she moved to the Erich Lindemann Mental Health Center on Staniford Street in Boston when a social worker found her a bed there.

Fed up again with her living situation, the prickly woman pines for the serenity she felt in the well-cleaned lounges at Logan, where she could always find leftover meals, an interesting conversation, and classical music to sooth her as she fell asleep.

Terminal A, where she used to sleep on occasion,

was recently razed to make way for a more modern facility. The cops are more likely to growl than they are to flash a smile. And her old acquaintances are nowhere to be found: Marie, a gray-haired woman who always wore a suit and said she was waiting to catch a plane to meet her grandson in New York; Elizabeth, who wore a turban and had food to share; and Peewee, an eccentric who often offered her cigarettes.

was recently razed to make way for a more modern facility. The cops are more likely to growl than they are to flash a smile. And her old acquaintances are nowhere to be found: Marie, a gray-haired woman who always wore a suit and said she was waiting to catch a plane to meet her grandson in New York; Elizabeth, who wore a turban and had food to share; and Peewee, an eccentric who often offered her cigarettes.On her first trip back to Logan in December, she wondered, "Where were the people? Where was the laughter? Where was the holiday happiness? . . . They've turned my home into a ghost town."

As time has passed, she feels more secure, as if life at Logan is returning to normal, or at least a new normal. There's the constant crawl of taxis. The great mix of people from all over the world. The food and financial opportunities. And, during the day, when there are even a few other homeless people, the old feeling comes back. "Who's to say I'm not a Parisian world traveler?" she said.

But, eyeing one of the muscular troopers toting a large assault rifle, she added: "I wouldn't dare come back to sleep."

With $6 in quarters in her purse and sipping from the cup of ice coffee, Jones smiled, watched the steady flow of pedestrians stream into the airport, and said, "My sense of optimism has returned. Logan is like America - the phoenix rising from the ashes."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Previous story:

AT LOGAN AIRPORT, A LOUNGE LIFE

HOMELESS WOMEN KEEP BAGS PACKED AT TERMINAL

By David Abel

Globe Staff

7/21/2001

For Judie Jones, home is a place that spans 2,400 acres and moves 80,000 people a day.

The petite 66-year-old from Australia is one of at least a half-dozen elderly women who spend nearly every night somewhere in the terminals of Logan International Airport.

"The skycaps, porters, and security people all come here to work, but, darling, this is my home," Jones says. "It's like Bob Hope used to say, but for me it's true: Airport waiting rooms are my real home."

Like the other "Logan ladies," as she calls them, Jones - a former substitute teacher and aspiring novelist - does her best to blend in. She dresses nicely, lugs around a Smarte Carte stacked with neatly arranged bags, and showers as often as possible.

"If someone asks what I'm doing, I say, `Oh, I'm just in from the Cape' or `I'm in from LA,' or, if I'm in the right mood, I say, `I'm just in from Paris.' "

Still, once the gates to most airlines have shut, the food courts have closed, and midnight passes, it's not hard to tell that the short woman stretched out comfortably across the vinyl seats of Terminal A intends to spend the night.

Officially the Massachusetts Port Authority doesn't allow anyone to live at the airport, which is open 24 hours a day. About a decade ago, when the homeless began descending on Logan in large numbers, Massport started sending them to shelters in agency-subsidized cabs. "This is a public facility; it's not a place for people to sleep," says Phil Orlandella, a Logan spokesman. "That is our policy and that will be our policy."

The state troopers who enforce the policy, however, use their discretion. They kick out the vast majority who hang around the airport, especially young men. But in spite of a memo this month warning that the homeless are "harassing employees and travelers," troopers let the older women stay.

"We call them our resident homeless," says Albert Manzi, who for years has worked the graveyard shift at Logan. "We do our best to get them to a better place, but some of them just like it here. They don't cause us any problems."

One trooper who asked not to be named said he won't evict certain people in the winter. Once, on a night when the temperature dropped below zero, a Massport official told him to remove one of the women. "I couldn't do that," he recalls. "I just took her to a different terminal."

Even among the slew of bonafide travelers sprawled out throughout the airport, Jones sticks out. She frequently quotes Shakespeare and compares herself to "a pushy broad like Ethel Merman." She cheerfully boasts about finding her colorful pants suit at the "Salvation Army Boutique." Her frizzy strawberry blond hair and craggy, sunburned skin frame a nearly toothless smile.

Manic, she rifles through crumpled dollar bills and cigarette butts stuffed in her plastic purse, sorts piles of papers in an old shopping bag, and scatters bags of junk food.

The commotion could easily give her away - and that would be a bad thing, she says. Like many homeless people, Jones loathes shelters, complaining they're overcrowded and dangerous. "There was so much brutality at the shelters that I couldn't stay there anymore," she says, calling Boston's Night Center "The Fright Center." "I thought, `Where else could I go that I would be shown humanity and treated with the graciousness of an international traveler?' "

At Logan, she feels safe, comfortable, and free to come and go as she pleases. She has also had good luck here. The troopers have only ordered her to leave once, she says. And Jones gets along well with them, enough so that she merrily introduces a reporter to troopers at the airport substation.

Arriving in the States shortly after divorcing her husband in 1988, she says, she has moved around, living everywhere from Las Vegas to San Antonio to Columbus, Ohio. Her last stop before Boston was Providence, where a string of bad luck first forced her onto the streets and where she discovered the perks of sleeping at an airport, she says.

A year ago, Jones caught a bus to Boston. She stayed in shelters for a few months until realizing she would be far more anonymous in the ever-churning world of Logan than at Providence's smaller T.F. Green Airport.

There are also distinct benefits to living at Logan. The airport is carpeted and clean, the bathrooms well maintained, there's air-conditioning, and the place abounds with leftover meals, sodas, and dropped change.

There are TVs to watch, what Jones calls "the best available selections of smokable cigarette butts in the whole of Boston," and there are often "presents" available, including airline personal care kits. "What a difference between the quality of the items handed out by Air France and the quality handed out at the shelters!" she says. "The deodorant is a brand-name spray, compared with that awful stick I've had to use."

There are even moneymaking opportunities. When she is low on cash, Jones walks around the airport, collecting scores of abandoned Smarte Cartes and returning each for a quarter. "I feel much more at home here because I can be a person of the world, not some statistic," she says, snatching another clump of butts from an ashtray outside Terminal E. "It's big and it's free and there's no oppression. It's really a fascinating place. The views are great, for which I pay nothing. I love watching the airplanes and the sunrise. And another thing: There's always someone to talk to."

Well after midnight, she runs into some of the other ladies. Marie, a gentle gray-haired woman in a rumpled blue suit with a pretty blouse, and a Filene's shopping bag on her wrist, could be anyone's grandmother.

"How's everything with you, Judie?" Marie says in a soft brogue, politely declining a stranger's offer to bring her some food and insisting she's about to catch a bus back to the city. When Jones leaves, she whispers, "The poor love. She doesn't know what day it is, she's been here so long."

Around the airport, Jones points to a few others who live at Logan but blend in with the late-night travelers. "That man is deaf," she points to an older man asleep in Terminal C. She opens the door to a bathroom in Terminal E, and a large 74-year-old woman named Mary is snoring on a bench next to a Smarte Carte.

Pointing to her resume, clumped with an old shopping bag filled with letters and articles she has written for Boston's homeless newspaper, Jones declares that she would make a perfect candidate for a job in Logan's public relations office. "How many people know this airport better than I do?" she says, adding that she has a master's degree. "How many are as attached to it as I am?"

After applying recently, Massport sent her a curt letter: "They basically said, `Thanks, but no thanks,' " she says.

Near bedtime around 3 a.m., on her way to her secret nook at the airport, a place she calls "No Man's Land," the old lady finds a spare pillow and blanket on a bench someone must have left from a recent flight. "Wonderful," she says. "Isn't life fun?"

Lying on a clean metal bench hidden away by two large display cases of model airplanes and a broad window looking over the great sprawl of Logan airport, Jones squints into the fluorescent lights and slips on a pair of old sunglasses. "Do I look glamorous or exhausted?" she jokes.

Then she shuts her eyes and tries to sleep, before the morning traffic wakes her.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe